Engineers Walk

Shipwright to Brunel

Bristol shipwrights were famed for their strong ships that could stand on their keels when the tide was out (they were Shipshape and Bristol Fashion). William Patterson was probably the greatest.

Patterson was born poor in Arbroath, Scotland in 1795 and was made a ward of a London slop-seller. At the age of 15 he was apprenticed to a shipbuilder in Rotherhithe and was later foreman to William Evans a well known ship builder. In 1822 he took charge of Evans yard and on his own account completed a steam packet for the Post Office, the Dasher. that gave him invaluable experience. The next year he moved to Bristol and became assistant to William Scott at his Wapping Yard, but he also had some modest shipping interests of his own. The following year he married Eliza Manning in St Mary Redcliffe Church and they were to raise 11 children. In 1830 Scott became bankrupt and in 1831 Patterson took ownership of the Wapping Yard that remained his until 1857. Patterson gained prominence in 1834 when he built the schooner Velox (154 tons). The ship was unusually slim for a Bristol ship and is described as a 'clipper model'. The press eulogised 'an improvement in the style of nautical architecture that must be hailed by everyone with satisfaction'.  His circle of friends included Thomas Guppy a marine engineer and businessman, Captain Claxton RN who was Quay Warden of Bristol Docks, and most importantly Isambard Kingdom Brunel. When the directors of the Great Western Railway decided in 1835 to build a steamship to 'extend' their railway to New York, the three Bristol men were appointed to make a tour of British Ports to gather information. Brunel designed a wooden ship with steam driven paddles, and the construction was entrusted to Patterson in his Wapping Yard. The Great Western, completed in 1838 was 236 feet long, 35 feet wide and weighed 1320 tons, two and a half times the weight of any ship built before it in Bristol.

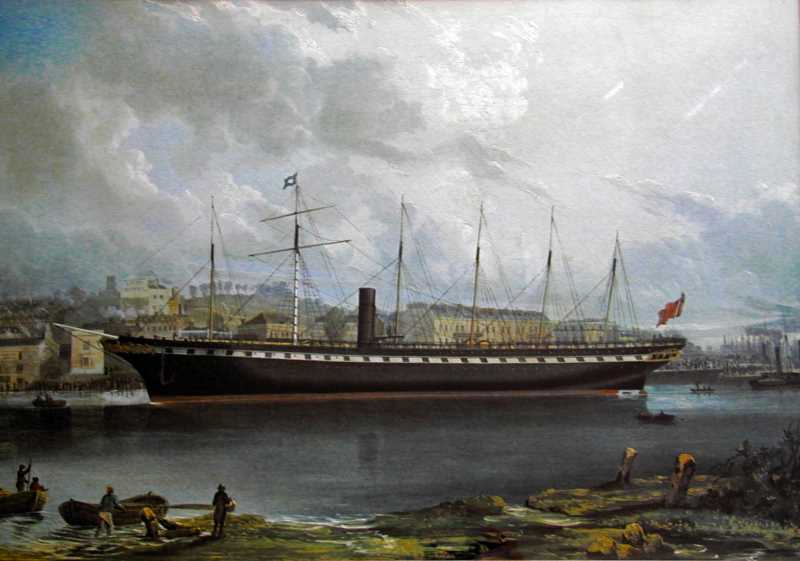

His circle of friends included Thomas Guppy a marine engineer and businessman, Captain Claxton RN who was Quay Warden of Bristol Docks, and most importantly Isambard Kingdom Brunel. When the directors of the Great Western Railway decided in 1835 to build a steamship to 'extend' their railway to New York, the three Bristol men were appointed to make a tour of British Ports to gather information. Brunel designed a wooden ship with steam driven paddles, and the construction was entrusted to Patterson in his Wapping Yard. The Great Western, completed in 1838 was 236 feet long, 35 feet wide and weighed 1320 tons, two and a half times the weight of any ship built before it in Bristol.

The Great Western failed to be the first steamship to cross the Atlantic westward by just 3 hours. That honour belongs to a much smaller vessel the Sirius that had set out several days earlier and had nearly run out of coal. However it was the Great Western that captured the imagination of New Yorkers and started the age of Trans Atlantic liners. The success of the Great Western made Patterson an acknowledged expert in building steamships and he was a consultant to other shipyards in Bristol and further afield.

The Great Western failed to be the first steamship to cross the Atlantic westward by just 3 hours. That honour belongs to a much smaller vessel the Sirius that had set out several days earlier and had nearly run out of coal. However it was the Great Western that captured the imagination of New Yorkers and started the age of Trans Atlantic liners. The success of the Great Western made Patterson an acknowledged expert in building steamships and he was a consultant to other shipyards in Bristol and further afield.

The directors of the Great Western Steamship Company required a sister ship to provide a frequent shuttle service. The construction committee of Patterson, Guppy, Claxton and Brunel recommended that the new ship should be built of iron. In 1839 Patterson made the first drawings of the hull, with concave bows at the waterline, and he must be given much of the credit for the elegant lines of the ship that finally emerged. The new ship was too large to be built in Patterson's yard so the Steamship Company leased and enlarged an existing dry dock (now known as the Great Western Yard) and it was here that Patterson built the Great Britain. Completed in 1843, she was 289 feet long by 50 feet wide and weighed 3270 tons, easily the biggest ship in the world. She was the first large ship to be built of iron, and the first large ship to be driven by a screw. She had the most powerful engine built up to that time, over 1000 horsepower, and the first balanced rudder. She had a double bottom and watertight compartments. She was the 'mother' of all modern ships.  Unfortunately the Great Britain was almost too large for Bristol Docks and there was great difficulty getting her out of the floating harbour. The business of building and operating large steamships soon moved to other ports.

Unfortunately the Great Britain was almost too large for Bristol Docks and there was great difficulty getting her out of the floating harbour. The business of building and operating large steamships soon moved to other ports.

William Patterson built many other ships in Bristol after the Great Britain, both in the Wapping yard, and from 1858 until 1865 in the Great Western Yard where he was assisted by his son William Jr. He experimented with mass production and in 1851 he completed 7 pilots of 26 tons in quick succession. Also in 1851 another ship over 3000 tons, the Demerara, was completed. She was to have engines fitted in another port, but while being towed down the Avon she was caught by the falling tide and broke her back. The ship was returned to Bristol and Patterson converted her to the largest sailing ship in the world. Other ventures included some steam warships for the Royal Navy during the Crimean War, some yachts including the Oriana for a member of the Royal Yacht Squadron and the Cyclone for himself, and three steamships for the Austrian Government! Writing in 1920 one of Patterson's granddaughters recalls his happy home life and his indulgence of his children and grandchildren. She also recalls that Patterson was invited to become a member of The Institution of Naval Architects when it was founded in 1860. Indeed the Institution's records do record him as a full member, recognising him as a naval architect as well as a shipbuilder. Patterson's wife died in 1865 and he retired to Liverpool where he died in 1869. Bibliography Bristol Shipbuilding in the Nineteenth Century - Grahame Farr Bristol Branch of The Historical Association 1971 Shipbuilding in the Port of Bristol - Grahame Farr National Maritime Museum 1977 The Iron Ship - Ewan Corlett Moonraker Press 1974 The Return of the Great Britain - Richard Gould Adams Weidenfield and Nicolson 1976 Brunel's Bristol - R A Buchanan and M Williams Redcliffe 1982 Brunel, The Great engineer - Tim Bryan Ian Allan 1999 Conways History of the Ship - The Advent of Steam - Editor Basil Greenhill Conway Marine Press 1993 SS Great Britain - Nicholas Fogg Great Britain Trust 1999 Bristol: Maritime City - Frank Shipsides and Bob Wall The Redcliffe Press Recollections by Maud Stanley Patterson (granddaughter) 1920 (Courtesy of SS Great Britain Trust) The restored Great Britain may be visited at the Great Western Yard where she was built. There is a photograph of William Patterson in Bristol City Museum that may be viewed by arrangement. John Coneybeare October 2005 |