Among his other activities, Marc Brunel designed machines for making army boots, knitting stockings, sawing timber, and printing, two suspension bridges at Ile de Bourbon near Mauritius and a floating landing stage at Liverpool. His greatest accomplishment and biggest project was the tunnel he constructed beneath the Thames between Rotherhithe and Wapping. He was knighted in 1841 for his contribution to British engineering having achieved little by way of financial success but gained the respect of his peers

On 1 November 1799, Marc married Sophia Kingdom (1775), the daughter of a Plymouth naval contractor. They had met in Rouen at the home of Marc's adopted family, the Carpentiers, and in 1793 they were engaged to be married. After Marc escaped to America, Sophia remained in France and when war with Britain broke out she was imprisoned as an enemy alien. She did not return home until 1795. Sophia endured a further three months in prison in 1821 when Marc Brunel's business failed and he was imprisoned for debt. Sophia remained with him throughout his ordeal. Marc's friends mounted a campaign to obtain a government grant of ٣, 000 to cover his debts and secure his release. The grant was partial compensation for the army-boots he had produced during the war but not been paid for. The Duke of Wellington intervened on his behalf after Marc threatened to emigrate to Russia and offer his services to Tsar Alexander unless the government paid him. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born in Portsea, Portsmouth on 9 April 1806. He was the only son of Marc and Sophia Brunel, and had two sisters, Sophia and Emma. Soon after Isambard's birth, the family left Portsmouth and moved to 10 Lindsey Row, Chelsea. As a boy, Marc Brunel had fallen out with his father, a prosperous farmer, because of his wish to become an engineer. He was pleased that his son Isambard showed an interest in engineering and taught him arithmetic, scale drawing and geometry at home. Despite the continuing financial struggle, Marc decided it was money well spent paying for his son's education and sent him to a highly regarded pre-preparatory boarding school in Hove. While he was there, Brunel undertook a survey of the town and impressed his classmates when he predicted the partial collapse of a building being constructed opposite the school. Isambard in the 1820s In 1820, Isambard Brunel travelled to France to acquire a more thorough academic grounding in his chosen field (there was no formal engineering training in Britain until the mid-nineteenth century). He studied at the College of Caen in Normandy and the Lycee Henri Quatre in Paris. He also served an apprenticeship with Abraham Louis Breguet, a master-craftsman skilled in the making of watches and scientific instruments. Brunel returned to Britain on 21 August 1822 and joined his father's drawing office at 29 Poultry Lane, London where he gained practical experience to complement his formal training. One of the projects his father passed over to him was the development of a gas engine that Marc hoped would come to replace the steam engine. Isambard did not abandon the attempt until the 1830s. While working in his father's office, Brunel also made regular visits to the works of the engineers Maudslay, Son and Field in Lambeth to widen his experience.

In 1820, Isambard Brunel travelled to France to acquire a more thorough academic grounding in his chosen field (there was no formal engineering training in Britain until the mid-nineteenth century). He studied at the College of Caen in Normandy and the Lycee Henri Quatre in Paris. He also served an apprenticeship with Abraham Louis Breguet, a master-craftsman skilled in the making of watches and scientific instruments. Brunel returned to Britain on 21 August 1822 and joined his father's drawing office at 29 Poultry Lane, London where he gained practical experience to complement his formal training. One of the projects his father passed over to him was the development of a gas engine that Marc hoped would come to replace the steam engine. Isambard did not abandon the attempt until the 1830s. While working in his father's office, Brunel also made regular visits to the works of the engineers Maudslay, Son and Field in Lambeth to widen his experience. Isambard was an ambitious young man, looking for fresh challenges, who chose for his motto En Avant - Get Going. He readily admitted to his need to be seen as important, perhaps in part compensating for his lack of physical stature (he was 5 ft 3 in/ 1.60 m tall). He wrote in his diary: "My love of glory is so strong, even on a dark night, riding home, when I pass some unknown person who perhaps does not even look at me, I catch myself trying to look big on my little pony - I often do the most silly, useless things to attract the attention of those I shall never see again."His admirers would later give him the nickname Little Giant. He was always willing to take risks and was prepared to invest his own money in his schemes as a point of principle, leading to occasional good fortune but also heavy losses.  In 1824, the Thames Tunnel Company was formed with Marc as its chief engineer and the Brunel family moved from fashionable Chelsea to the less salubrious Blackfriars. Construction of the tunnel began on 2 March 1825. Isambard was formally appointed its resident engineer on 3 January 1827. Despite his youth and lack of experience, he had been supervising work on the project for some time, gaining the respect of his men through his dedication and bravery. On 10 November 1827, he organised a grand banquet in the tunnel to celebrate the resumption of work after a serious flood six months previously. There were 50 invited guests and 120 miners also attended. The walls were hung with crimson drapes and candles blazed while the band of the Coldstream Guards played. This was an early example of his awareness of the value of making a grand public gesture to generate interest in his work. Through his involvement with the Thames Tunnel, he discovered his self-confidence and capacity for leadership, and he emerged from the project as a fully equipped engineer.

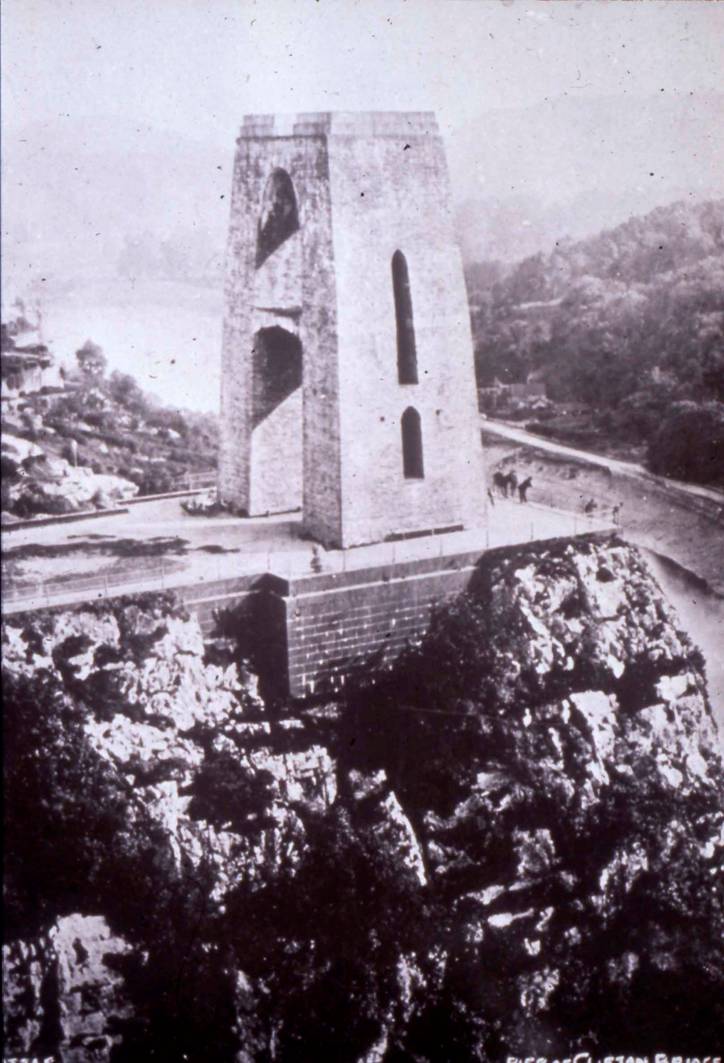

In 1824, the Thames Tunnel Company was formed with Marc as its chief engineer and the Brunel family moved from fashionable Chelsea to the less salubrious Blackfriars. Construction of the tunnel began on 2 March 1825. Isambard was formally appointed its resident engineer on 3 January 1827. Despite his youth and lack of experience, he had been supervising work on the project for some time, gaining the respect of his men through his dedication and bravery. On 10 November 1827, he organised a grand banquet in the tunnel to celebrate the resumption of work after a serious flood six months previously. There were 50 invited guests and 120 miners also attended. The walls were hung with crimson drapes and candles blazed while the band of the Coldstream Guards played. This was an early example of his awareness of the value of making a grand public gesture to generate interest in his work. Through his involvement with the Thames Tunnel, he discovered his self-confidence and capacity for leadership, and he emerged from the project as a fully equipped engineer. In January 1828, Brunel was seriously injured during a major flood at the tunnel in which six men drowned. His knee was badly damaged by a falling timber and he also suffered internal injuries. When he was well enough to travel, Brunel spent his convalescence in Brighton and Bristol, where he heard of plans to build a bridge across the Avon at Clifton. In March 1831, one of Brunel's designs submitted for the second Clifton Suspension Bridge competition was formally awarded first prize and a ceremony to mark the laying of the foundation stone on the Clifton side of the gorge took place on 21 June. In October that year, Brunel was sworn in as a special constable during the Bristol Riots, which were centred on Queen Square. He actually arrested a man who he unwittingly passed over to another rioter disguised as a constable. The disruption caused by the rioting contributed to delays in the construction of the bridge as business confidence in the city fell. Although work was eventually resumed and the foundation stone for the abutment on the Leigh Woods side of the gorge was laid on 27 August 1836. However by 1843, with only the towers built, funds were exhausted and work stopped. After Brunel's death, the Institution of Civil Engineers raised funds to complete the bridge in memory of Brunel. Sir John Hawkshaw and Henry Barlow modified the design and achieved this in 1864.

In January 1828, Brunel was seriously injured during a major flood at the tunnel in which six men drowned. His knee was badly damaged by a falling timber and he also suffered internal injuries. When he was well enough to travel, Brunel spent his convalescence in Brighton and Bristol, where he heard of plans to build a bridge across the Avon at Clifton. In March 1831, one of Brunel's designs submitted for the second Clifton Suspension Bridge competition was formally awarded first prize and a ceremony to mark the laying of the foundation stone on the Clifton side of the gorge took place on 21 June. In October that year, Brunel was sworn in as a special constable during the Bristol Riots, which were centred on Queen Square. He actually arrested a man who he unwittingly passed over to another rioter disguised as a constable. The disruption caused by the rioting contributed to delays in the construction of the bridge as business confidence in the city fell. Although work was eventually resumed and the foundation stone for the abutment on the Leigh Woods side of the gorge was laid on 27 August 1836. However by 1843, with only the towers built, funds were exhausted and work stopped. After Brunel's death, the Institution of Civil Engineers raised funds to complete the bridge in memory of Brunel. Sir John Hawkshaw and Henry Barlow modified the design and achieved this in 1864.

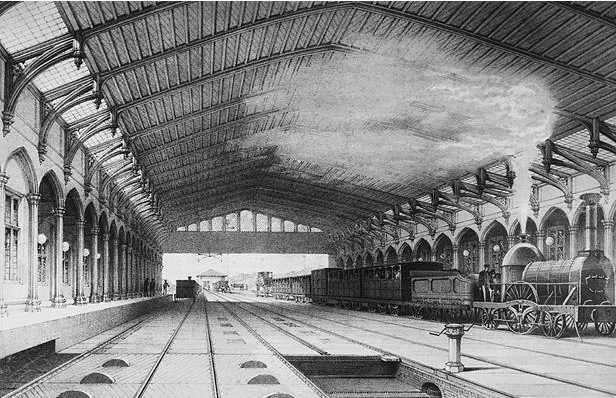

The 1830'sIn 1832, Brunel began his association with the Bristol Docks Company where he was engaged with schemes for improving and modernising the facilities for the next 15 years. He worked at other docks over the years including Plymouth, Cardiff, Brentford and Milford Haven.In March 1833, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the newly formed Great Western Railway and started surveying the route from London to Bristol. The wealthy Guppy family had engineering interests and were friends of the Brunels with homes in Bristol and London. Thomas Guppy was a Director and an investor in the railway company and later in the steamship company, who cooperated closely with Brunel. Brunel had no previous experience in railway engineering but the directors were impressed by his enthusiasm and self-assurance. He had made his first journey by train on 5 December 1831 and wrote in his diary, alongside a series of wavering lines and circles: "I record this specimen of the shaking on Manchester railway. The time is not far off when we shall be able to take our coffee and write while going noiselessly and smoothly at 45 miles per hour - let me try."  The Second Great Western Railway Bill was passed in August 1835 and Brunel's proposal to use a broad gauge system, which he felt would provide faster and smoother journeys, was accepted in October. That same year Brunel was appointed engineer for the Cheltenham & Great Western Union, Bristol & Exeter, Bristol & Gloucester, and Merthyr & Cardiff railways. He would hold many engineering appointments with various railway companies during his career, including projects in Italy and India. He was usually involved in every detail of their construction, not just the route, track and engines, but the architecture of the stations (including Bristol Temple Meads), the colour of the livery and the decorative details. He would often be engaged in a number of major projects at any one time, adding to the pressures upon him but satisfying his love of work. The London-Bristol section of the Great Western route was opened on 30 June 1841.

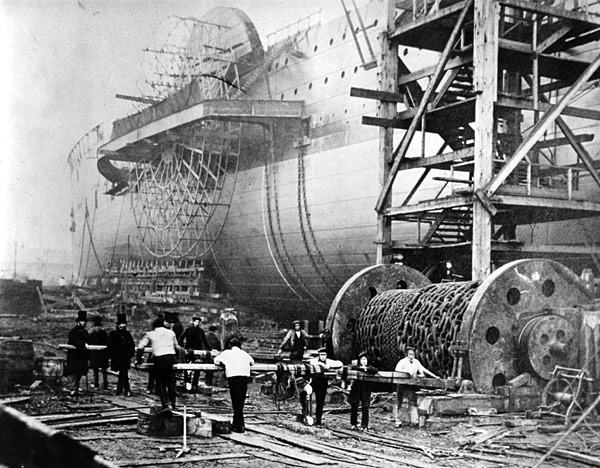

The Second Great Western Railway Bill was passed in August 1835 and Brunel's proposal to use a broad gauge system, which he felt would provide faster and smoother journeys, was accepted in October. That same year Brunel was appointed engineer for the Cheltenham & Great Western Union, Bristol & Exeter, Bristol & Gloucester, and Merthyr & Cardiff railways. He would hold many engineering appointments with various railway companies during his career, including projects in Italy and India. He was usually involved in every detail of their construction, not just the route, track and engines, but the architecture of the stations (including Bristol Temple Meads), the colour of the livery and the decorative details. He would often be engaged in a number of major projects at any one time, adding to the pressures upon him but satisfying his love of work. The London-Bristol section of the Great Western route was opened on 30 June 1841. In 1836, Brunel was appointed engineer of the Great Western Steamship Company and work began in Bristol on his first ship design - SS Great Western. The ship formed part of a proposed integrated transport system that would bring people from London to Bristol by train, to the dockside by coach and to New York by steamship. The hull was launched on 19 July 1837 and work commenced that same year on building the Royal Western Hotel to accommodate passengers. The Great Western's maiden trans-Atlantic voyage in 1838 took 15 days. Construction began on a much larger sister ship, the SS Great Britain, in 1839 at the Great Western Dockyard. Following an occasionally distinguished but often ill-fated career, the ship returned to Bristol in 1970 and is now one of the icons of the city.

In 1836, Brunel was appointed engineer of the Great Western Steamship Company and work began in Bristol on his first ship design - SS Great Western. The ship formed part of a proposed integrated transport system that would bring people from London to Bristol by train, to the dockside by coach and to New York by steamship. The hull was launched on 19 July 1837 and work commenced that same year on building the Royal Western Hotel to accommodate passengers. The Great Western's maiden trans-Atlantic voyage in 1838 took 15 days. Construction began on a much larger sister ship, the SS Great Britain, in 1839 at the Great Western Dockyard. Following an occasionally distinguished but often ill-fated career, the ship returned to Bristol in 1970 and is now one of the icons of the city. The Second Great Western Railway Bill was passed in August 1835 and Brunel-s proposal to use a broad gauge system, which he felt would provide faster and smoother journeys, was accepted in October. That same year Brunel was appointed engineer for the Cheltenham & Great Western Union, Bristol & Exeter, Bristol & Gloucester, and Merthyr & Cardiff railways. He would hold many engineering appointments with various railway companies during his career, including projects in Italy and India. He was usually involved in every detail of their construction, not just the route, track and engines, but the architecture of the stations (including Bristol Temple Meads), the colour of the livery and the decorative details. He would often be engaged in a number of major projects at any one time, adding to the pressures upon him but satisfying his love of work. The London-Bristol section of the Great Western route was opened on 30 June 1841.

The Second Great Western Railway Bill was passed in August 1835 and Brunel-s proposal to use a broad gauge system, which he felt would provide faster and smoother journeys, was accepted in October. That same year Brunel was appointed engineer for the Cheltenham & Great Western Union, Bristol & Exeter, Bristol & Gloucester, and Merthyr & Cardiff railways. He would hold many engineering appointments with various railway companies during his career, including projects in Italy and India. He was usually involved in every detail of their construction, not just the route, track and engines, but the architecture of the stations (including Bristol Temple Meads), the colour of the livery and the decorative details. He would often be engaged in a number of major projects at any one time, adding to the pressures upon him but satisfying his love of work. The London-Bristol section of the Great Western route was opened on 30 June 1841. In 1836, Brunel was appointed engineer of the Great Western Steamship Company and work began in Bristol on his first ship design - SS Great Western.

The ship formed part of a proposed integrated transport system that would bring people from London to Bristol by train, to the dockside by coach and to New

York by steamship. The hull was launched on 19 July 1837 and work commenced that same year on building the Royal Western Hotel to accommodate passengers.

The Great Western's maiden trans-Atlantic voyage in 1838 took 15 days. Construction began on a much larger sister ship, the SS Great Britain, in 1839

at the Great Western Dockyard. Following an occasionally distinguished but often ill-fated career, the ship returned to Bristol in 1970 and is now

one of the icons of the city.

In 1836, Brunel was appointed engineer of the Great Western Steamship Company and work began in Bristol on his first ship design - SS Great Western.

The ship formed part of a proposed integrated transport system that would bring people from London to Bristol by train, to the dockside by coach and to New

York by steamship. The hull was launched on 19 July 1837 and work commenced that same year on building the Royal Western Hotel to accommodate passengers.

The Great Western's maiden trans-Atlantic voyage in 1838 took 15 days. Construction began on a much larger sister ship, the SS Great Britain, in 1839

at the Great Western Dockyard. Following an occasionally distinguished but often ill-fated career, the ship returned to Bristol in 1970 and is now

one of the icons of the city. On 5 July 1836, Brunel married Mary Horsley and the couple set up home at 18 Duke Street, Westminster. They had three children Isambard, who became a lawyer

and his father's biographer; Florence Mary who married a teacher at Eton and Henry Marc, who became an engineer. His friend and colleague William Dawes

had introduced Brunel to the Horsley family in 1832, and he had often visited their home where he enjoyed amateur theatricals, charades, music and oratories in

his rare moments of leisure. Brunel had had a number of romantic interludes but had always declared that he would only marry a woman with money and musical

talent. As Mary had neither and, it has been said, had 'nothing to be proud of but her face' it can be assumed that Brunel married for love.

Mary would become a popular hostess, entertaining the cream of fashionable London society at their home and providing what Adrian Vaughan has described as

&'39an oasis of culture' for Brunel to occasionally return to. Her brother, the artist John Horsley, was a close friend of Brunel and painted his

portrait.

On 5 July 1836, Brunel married Mary Horsley and the couple set up home at 18 Duke Street, Westminster. They had three children Isambard, who became a lawyer

and his father's biographer; Florence Mary who married a teacher at Eton and Henry Marc, who became an engineer. His friend and colleague William Dawes

had introduced Brunel to the Horsley family in 1832, and he had often visited their home where he enjoyed amateur theatricals, charades, music and oratories in

his rare moments of leisure. Brunel had had a number of romantic interludes but had always declared that he would only marry a woman with money and musical

talent. As Mary had neither and, it has been said, had 'nothing to be proud of but her face' it can be assumed that Brunel married for love.

Mary would become a popular hostess, entertaining the cream of fashionable London society at their home and providing what Adrian Vaughan has described as

&'39an oasis of culture' for Brunel to occasionally return to. Her brother, the artist John Horsley, was a close friend of Brunel and painted his

portrait.

The 1840s and 1850sBrunel worked long hours and was frequently away on business, but still found time to entertain his children with nursery games and conjuring. In 1843, he accidentally swallowed a half-sovereign he was using in one of his tricks. It lodged in his windpipe and threatened to choke him to death. A tracheotomy was performed by a leading surgeon with two-foot long forceps but was unsuccessful. Showing his ingenuity and sang-froid,

Brunel devised a board, pivoted between two uprights, to which he was strapped and rapidly turned head over heels. The centrifugal force dislodged the coin,

which dropped from his mouth. A tracheotomy was performed by a leading surgeon with two-foot long forceps but was unsuccessful. Showing his ingenuity and sang-froid,

Brunel devised a board, pivoted between two uprights, to which he was strapped and rapidly turned head over heels. The centrifugal force dislodged the coin,

which dropped from his mouth.In 1850, Brunel became involved in preparations for the Great Exhibition of Science and Industry of All Nations to be held in Hyde Park the following year. He contributed to early designs for an exhibition space and in the arrangements for the opening parade. When Paxtonís Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham, Brunel designed two water towers for the site. In 1853, work began on Brunel's biggest maritime project: the SS Great Eastern. At the same time, Brunel was also supervising the construction of another of his engineering triumphs, the Royal Albert Bridge which carried the Cornwall Railway line over the River Tamar at Saltash. This was completed in 1859. In February 1855, Brunel was invited by the Permanent Under Secretary at the War Office, Sir Benjamin Hawes (husband of his sister Sophia), to design a pre-fabricated hospital for use in the Crimea that could be built in Britain and shipped out for speedy erection at a chosen site. The design took six days to complete and the parts reached Renkioi in the Dardanelles in May that year. By July it was ready to admit its first 300 patients and by December had reached its capacity of 1,000 beds. On his doctor's advice, Brunel travelled to the Alps, Vichy and Egypt during 1858. He was suffering from Bright-s disease and had endured years of physical and mental strain. On Christmas Day he dined in Cairo with Robert Stephenson, his old friend and colleague, who had similarly ruined his health through overwork. Despite deriving some initial benefit from the change of scene, when Brunel returned to Britain the stress associated with the SS Great Eastern project intensified and he collapsed with a stroke on 5 September 1859. He died at his Westminster home ten days later. Brunel was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery on 20 September 1859. The route to the cemetery was lined with thousands of railwaymen and members of the public. His friend and colleague Daniel Gooch wrote in his diary: "I have lost my oldest and best friend. By his death the greatest of England's engineers was lost, the man with the greatest originality of thought and power of execution, bold in his plans but right. The commercial world thought him extravagant; but although he was so, things are not done by those who sit down and count the cost of every thought and act."   John Coneybeare March 2011 |